16.1.3 POJA-L7023+7025 Calcification process in bone 2

16.1.3 POJA-L7023+7025 Calcification process in bone 2

Title: Calcification process in bone 2

Description:

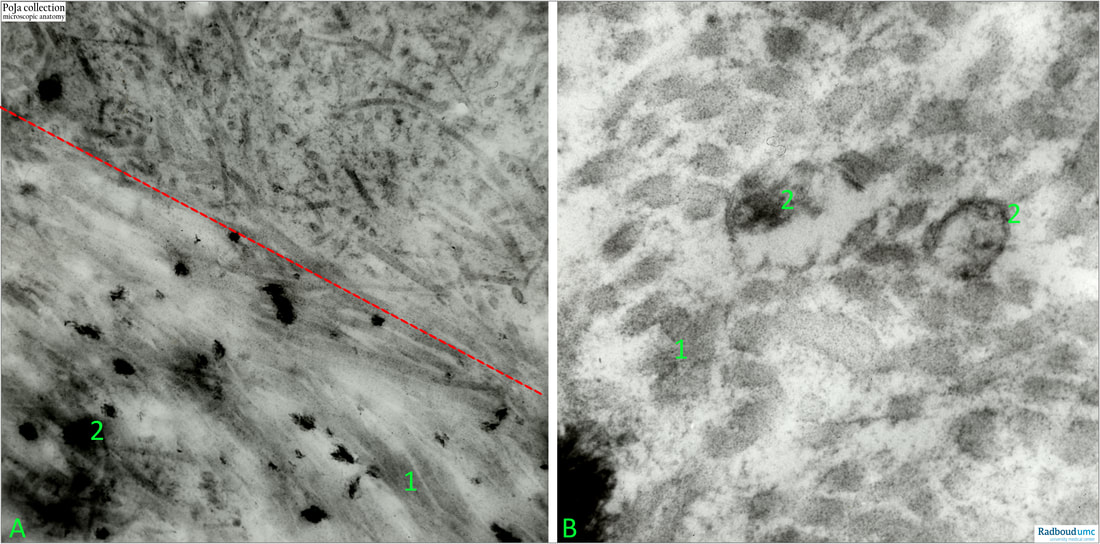

Bone implantation in rabbit.

(A): Left low: furthest away from the implantation. Low magnification. Note the distribution density difference of the collagen fibrils in lower half versus upper half of the picture. Top right is close to the implantation of the bone. (2) in (A): are free hydroxyapatite NOT arranged and stored as crystals in vesicles.

(B): High magnication illustrating the collagen fibrils, and the vesicles with calcium crystals

(1): Collagen fibrils.

(2): Calcium crystals (in vesicles).

Background:

Bone is a compound tissue consisting of cells, matrix (collagen and non-collagenous proteins), mineral and water. The mineral is hydroxyapatite, which is a naturally occurring crystalline calcium phosphate. As the matrix matures hydroxyapatite microcrystals are organised into a sophisticated composite in the collagen layer and the presence of repeating charge alignment on collagen suggested that a nucleation lattice is present.

Collagen type I acts as a template for the precipitation of the inorganic matter and together with other proteins (i.e. bone sialoprotein, osteocalcin, osteonectin, alkaline phosphatase) have a key role in the mineralisation process. Some of these proteins have calcium binding domains, which in turn bind to phosphate ions, allowing the formation of apatite crystals.

The bone synthesis is characterised by massive numbers of membrane vesicles shed at the apical surface of the secreting osteoblasts. The shed vesicles contain small calcium phosphate crystal precursors and lipids that are capable of attracting calcium. The deposition of calcium and phosphate into hydroxyapatite occurs initially by nucleation of these extracellular, lipid bilayer-enclosed microstructures (ALP-rich matrix vesicles 50-250 nm) and collagen fibrils. Being important features of bone, these vesicles are not the only single force that drives dense mineral accumulation to completion. Calcium phosphate is found to enter into small longitudinal orientated gaps in the collagen fibril where it crystallises into small thin needles. It is proven that the process is guided in a physico-chemical way and not influenced by bioactive collagen molecules. The outgrowth of the needles results in a thin plate of calcium phosphate pushing away the surrounding collagen. Replacement of the hydroxyl ion group by fluoride, chloride or carbonate groups results in an identical rate of crystallisation. (Intermolecular channels direct crystal orientation in mineralized collagen. YiFei Xu et al. Nat Commun 2020

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-18846-2

See also:

Keywords/Mesh: locomotor system, bone, calcium crystal, collagen fibril, mineralisation, bone implant, electron microscopy, POJA collection

Title: Calcification process in bone 2

Description:

Bone implantation in rabbit.

(A): Left low: furthest away from the implantation. Low magnification. Note the distribution density difference of the collagen fibrils in lower half versus upper half of the picture. Top right is close to the implantation of the bone. (2) in (A): are free hydroxyapatite NOT arranged and stored as crystals in vesicles.

(B): High magnication illustrating the collagen fibrils, and the vesicles with calcium crystals

(1): Collagen fibrils.

(2): Calcium crystals (in vesicles).

Background:

Bone is a compound tissue consisting of cells, matrix (collagen and non-collagenous proteins), mineral and water. The mineral is hydroxyapatite, which is a naturally occurring crystalline calcium phosphate. As the matrix matures hydroxyapatite microcrystals are organised into a sophisticated composite in the collagen layer and the presence of repeating charge alignment on collagen suggested that a nucleation lattice is present.

Collagen type I acts as a template for the precipitation of the inorganic matter and together with other proteins (i.e. bone sialoprotein, osteocalcin, osteonectin, alkaline phosphatase) have a key role in the mineralisation process. Some of these proteins have calcium binding domains, which in turn bind to phosphate ions, allowing the formation of apatite crystals.

The bone synthesis is characterised by massive numbers of membrane vesicles shed at the apical surface of the secreting osteoblasts. The shed vesicles contain small calcium phosphate crystal precursors and lipids that are capable of attracting calcium. The deposition of calcium and phosphate into hydroxyapatite occurs initially by nucleation of these extracellular, lipid bilayer-enclosed microstructures (ALP-rich matrix vesicles 50-250 nm) and collagen fibrils. Being important features of bone, these vesicles are not the only single force that drives dense mineral accumulation to completion. Calcium phosphate is found to enter into small longitudinal orientated gaps in the collagen fibril where it crystallises into small thin needles. It is proven that the process is guided in a physico-chemical way and not influenced by bioactive collagen molecules. The outgrowth of the needles results in a thin plate of calcium phosphate pushing away the surrounding collagen. Replacement of the hydroxyl ion group by fluoride, chloride or carbonate groups results in an identical rate of crystallisation. (Intermolecular channels direct crystal orientation in mineralized collagen. YiFei Xu et al. Nat Commun 2020

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-18846-2

See also:

Keywords/Mesh: locomotor system, bone, calcium crystal, collagen fibril, mineralisation, bone implant, electron microscopy, POJA collection